Last week, the Centre held a discussion event about the relationship between Britain and Germany during and since the First World War. With the help of several invited speakers, we discussed the impact of war on the German community in Britain, the realities of internment and the changing patterns of Germanophobia and Germanophilia in the twentieth century.

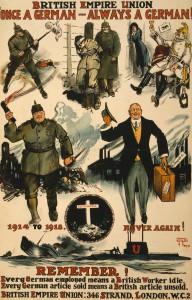

Professor Panikos Panayi of De Montfort University presented some fascinating material on the changing attitudes to Germany on the part of the British people, including examples and commentary on phenomena such as the proliferation of anti-German invasion literature such as the Invasion of 1910 by William Le Quex, the use of stereotypes in propaganda as well as broadly positive stereotypes of Germans, such as a tendency to efficiency and skill in engineering.

Penny Walker from the Highfields Association of Residents and Tenants in Leicester, discussed her project How Saxby Street Got Its Name, which tells the story of how German-sounding streets in Leicester, including Hanover Street, Saxe-Coburg Street and Gotha Street were Anglicised during the war and are still known as Andover Street, Saxby Street and Gotham Street.

Louise Page, a playwright from Derbyshire, discussed her extensive interest in the topic, including her plans for projects that examine how the spread of anti-German feeling was experienced by members of the German diaspora in Britain. Her focus in on the personal, such as the sensitivity that people felt about their German names, and on the continuity of such attitudes towards other people today.

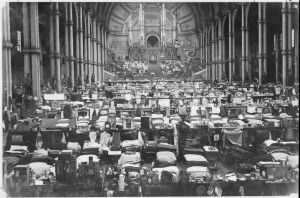

Dr Maggie Butt, of Middlesex University, gave a presentation of her work on the internment camp at Alexandra Palace. From 1915 to 1919 it was used as a camp for civilian internees, who were billeted according to class. Her project includes retellings of the first-hand stories of several specific internees, including the Old Harrovian R.H. Sauter and the anarchist intellectual Rudolf Rocker.

Andy Barrett of Excavate Community Theatre was accompanied by Heinke and Joyce from the Lutheran congregation in Aspley. They have access to a community of elders from the German community who have many stories to tell. They would like to record these stories and present them in a performative way.

Dr Claudia Sternberg from the University of Leeds told the story of Sophie Hellweg and Frank West, a British-German couple whose lives embodied some of the pressure that was felt by the people in mixed marriages during and after wartime.

Following these excellent presentations, we held a discussion about the topics and themes that had been raised. This included the relative strangeness of the British experience, with largely fixed borders, as compared to the more fluid nation-states of continental Europe, including Germany. This has contributed to a particular sense of the meaning of the First and Second World Wars that is not necessarily shared on the continent and which is having an impact on the progress of the Centenary of World War One. There is a great desire on the part of the public to learn more about the relationship between Britain and Germany (and between British and German people) that is shared by professional researchers. It is not necessarily shared by official bodies and some delegates reported difficulties in getting public authorities to support their work.

Nevertheless, we finished the discussions resolved to do more to explore this fascinating area of history. The event provided an excellent opportunity for delegates to share contact details and to make plans for collaboration. We are now planning to develop a pattern of projects that will explore and share these histories and ensure that the Centenary does not pass without addressing them.

If you’re interesting in developing a project about the German-British experience, or have a story to share, please get in touch.