The Centre for Hidden Histories is proud to present a public talk on the subject of British Public Parks and the First World War. Professor Paul Elliott, of the University of Derby, will give the talk at Derby Quad on Wednesday 27th May at 7pm. Here, Professor Elliott introduces some of the themes that he will cover in his talk.

On 16 December 1914 German shells thudded into Scarborough from the sea, aimed at a Naval Wireless Station at the top of Falsgrave Park. In all, the bombardment killed 17 people including a 14 month old child who had been in Westbourne Park. Apart from this highly unusual episode in the home front context, public parks were rarely, of course, the targets of German bombs, although perhaps they ought to have been, as they were playing their role in the war effort.

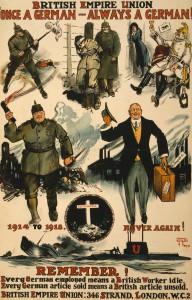

Public reaction to the conflict changed over the course of the war, with propaganda and rumour fostering patriotism and hatred of the enemy whilst the ethic of volunteerism and the rhetoric of sacrifice were prominent in debates over where the burdens of war should fall and documented in public discourse, as well as the influence of religious ideas. As the war drew to a climax, tensions about the distribution of sacrifices threatened to tear society apart, whilst victory and the processes of commemoration helped create a fiction of a society united in grief.

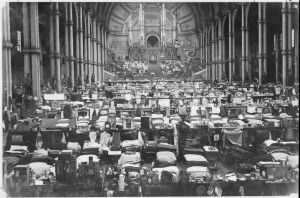

This talk will argue that public parks were caught up in some of these reactions and ambiguities, and were utilised both in support of the war effort in various ways and also sometimes as places where resistance to the war and its consequences occurred. The recruitment of hundreds of thousands of men for the armed forces, food shortages and rationing, the assumption of male work roles by numerous women, all impacted upon urban parks and green spaces. As we shall see, public parks in Derby and other places were requisitioned for various purposes including military (such as anti- Zeppelin and aircraft guns), defensive, governmental, medical and for food production, particularly after the Defence of the Realm Act or (DORA) was passed. They also played an important role in maintaining morale when some other forms of recreation were curtailed such as organised sports like football and rugby. At the same time, parks were places where civilian and military populations on leave or recuperating could temporarily escape from some of the demands of war and even resist authority. On occasion they served as venues for anti-war and pacifist meetings and demonstrations too.

This talk will argue that public parks were caught up in some of these reactions and ambiguities, and were utilised both in support of the war effort in various ways and also sometimes as places where resistance to the war and its consequences occurred. The recruitment of hundreds of thousands of men for the armed forces, food shortages and rationing, the assumption of male work roles by numerous women, all impacted upon urban parks and green spaces. As we shall see, public parks in Derby and other places were requisitioned for various purposes including military (such as anti- Zeppelin and aircraft guns), defensive, governmental, medical and for food production, particularly after the Defence of the Realm Act or (DORA) was passed. They also played an important role in maintaining morale when some other forms of recreation were curtailed such as organised sports like football and rugby. At the same time, parks were places where civilian and military populations on leave or recuperating could temporarily escape from some of the demands of war and even resist authority. On occasion they served as venues for anti-war and pacifist meetings and demonstrations too.

The event is free but spaces are limited so if you are interested in attending, please let us know by emailing hiddenhistories@nottingham.ac.uk

Recent years have seen a revolution in family history and amateur genealogy. The possibilities created by broadband internet, the digitisation of official and parish records and the advent of crowdsourcing have created an unprecedented boom in the pursuit of private histories. The popularity of programmes such as Who Do You Think You Are? testifies to the the mainstream success of this once esoteric hobby. It has given more people a basic grounding in historical enquiry, and has encouraged the development of skills such as research, paleography and metadata tagging. It also has led to the creation of mini-archives, comprising collections of documents, photographs, artefacts and secondary material such as family trees and published (traditionally and online) material.

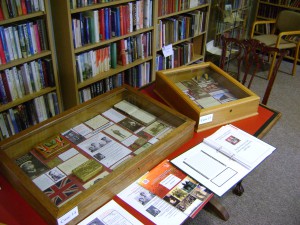

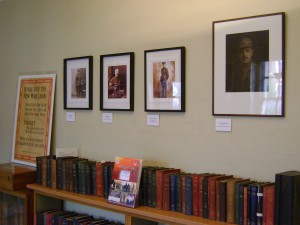

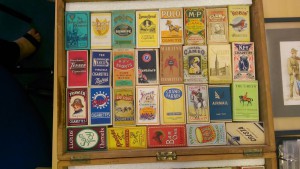

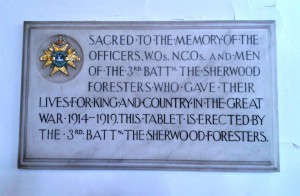

Recent years have seen a revolution in family history and amateur genealogy. The possibilities created by broadband internet, the digitisation of official and parish records and the advent of crowdsourcing have created an unprecedented boom in the pursuit of private histories. The popularity of programmes such as Who Do You Think You Are? testifies to the the mainstream success of this once esoteric hobby. It has given more people a basic grounding in historical enquiry, and has encouraged the development of skills such as research, paleography and metadata tagging. It also has led to the creation of mini-archives, comprising collections of documents, photographs, artefacts and secondary material such as family trees and published (traditionally and online) material. During the course of our project we have encountered people who have undertaken such research and who have gathered documents, photographs and other artefacts. They are often older members of the household who have embarked on their project in retirement and have been motivated to do so because they have a personal memory of some of the individuals concerned, assuming a combatant birth year range of c1868-1902. As this generation ages, we will encounter a ‘succession problem’ of what to do with such collections that are too small and/or esoteric to be absorbed into mainstream collections. A related issue is the atomised nature of these items. They reside in spare rooms, on living room walls and in attics and could be hiding information useful to professional historians. These archives, a combination of documentary information and material artefacts are of intense personal value to the people who have carefully curated them. But they have other value too. They are of use to professional historians who can use them in aggregate to build a picture of the social past.

During the course of our project we have encountered people who have undertaken such research and who have gathered documents, photographs and other artefacts. They are often older members of the household who have embarked on their project in retirement and have been motivated to do so because they have a personal memory of some of the individuals concerned, assuming a combatant birth year range of c1868-1902. As this generation ages, we will encounter a ‘succession problem’ of what to do with such collections that are too small and/or esoteric to be absorbed into mainstream collections. A related issue is the atomised nature of these items. They reside in spare rooms, on living room walls and in attics and could be hiding information useful to professional historians. These archives, a combination of documentary information and material artefacts are of intense personal value to the people who have carefully curated them. But they have other value too. They are of use to professional historians who can use them in aggregate to build a picture of the social past.

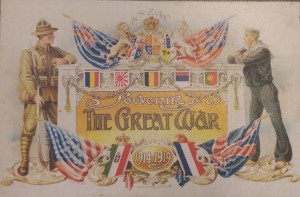

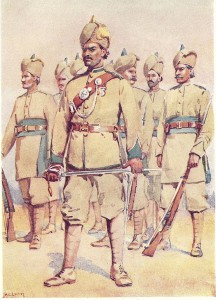

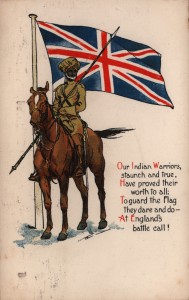

One hundred years ago, undivided India provided Britain with a massive volunteer army in its hour of need. From 1914-1918 close to 1.5 million Indians served, fighting in all the major theatres of war from Flanders Fields in Belgium to the Mesopotamian oil fields of present day Iraq. One in six of the service personnel under British command was from the Indian subcontinent. Because of this there are many connections to be made between Britain’s South Asian communities and this landmark conflict.

One hundred years ago, undivided India provided Britain with a massive volunteer army in its hour of need. From 1914-1918 close to 1.5 million Indians served, fighting in all the major theatres of war from Flanders Fields in Belgium to the Mesopotamian oil fields of present day Iraq. One in six of the service personnel under British command was from the Indian subcontinent. Because of this there are many connections to be made between Britain’s South Asian communities and this landmark conflict.

During the event there will be a series of presentations and participants will have the opportunity to share their own work, meet others working on projects, and discuss with staff from the WW1 Engagement Centres how to develop or expand projects or research.

During the event there will be a series of presentations and participants will have the opportunity to share their own work, meet others working on projects, and discuss with staff from the WW1 Engagement Centres how to develop or expand projects or research.