As the centenary of the First World War sees family history come of age Michael Noble asks, what opportunities does this offer?

Recent years have  seen a revolution in family history and amateur genealogy. The possibilities created by broadband internet, the digitisation of official and parish records and the advent of crowdsourcing have created an unprecedented boom in the pursuit of private histories. The popularity of programmes such as Who Do You Think You Are? testifies to the the mainstream success of this once esoteric hobby.

seen a revolution in family history and amateur genealogy. The possibilities created by broadband internet, the digitisation of official and parish records and the advent of crowdsourcing have created an unprecedented boom in the pursuit of private histories. The popularity of programmes such as Who Do You Think You Are? testifies to the the mainstream success of this once esoteric hobby.

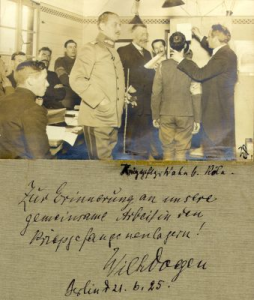

During the course of our project we have encountered people who have undertaken family history research and who have gathered documents, photographs and other artefacts. They are often older members of the household who have embarked on their project in retirement and have been motivated to do so because they have a personal memory of some of the individuals concerned, assuming a combatant birth year range from the 1860s to the turn of the twentieth century. As this generation ages, we will encounter a ‘succession problem’ of what to do with such collections that are too small and/or esoteric to be absorbed into mainstream collections. A related issue is the atomised nature of these items. They reside in spare rooms, on living room walls and in attics and could be hiding information useful to professional historians.

Two key problems:

1. How do we ensure the preservation of historically valuable collections?

2. How do we give access to them to professional historians and other researchers?

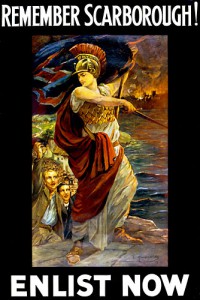

These are questions for family history in general but the centenary of the war can bring it into focus. The world wars, like items such as the 1901 census, act as ‘informational nodes’ for family historians and many of their researches converge on this event. This, combined with media coverage of the centenary and crowdsourcing schemes such as Operation War Diary and Lives of the First World War, offer an opportunity to test the value of family history and a chance to make it useful to mainstream historians without, I hope, robbing it of its very real value to those individuals who have been doing so much work in this area in their free time.

We are very keen to hear from people who have found or kept interesting First World War items and who are interesting in using them to foster a better understanding of the war, its effects and of the role of memory in family history and identity. We’re planning some events for 2015 that will help to ensure that these precious items continue to be of value as the war fades into history. If you have something to share, please get in touch.

We are very keen to hear from people who have found or kept interesting First World War items and who are interesting in using them to foster a better understanding of the war, its effects and of the role of memory in family history and identity. We’re planning some events for 2015 that will help to ensure that these precious items continue to be of value as the war fades into history. If you have something to share, please get in touch.

wonderful audio collection of wartime memories

wonderful audio collection of wartime memories

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

ouching without being sentimental

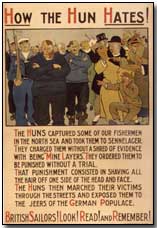

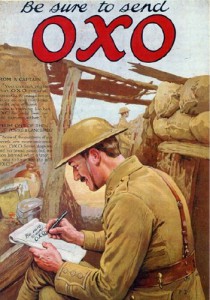

ouching without being sentimental ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.

ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.