Here’s an interesting piece by University of Nottingham engineer Mike Fay on the development of the gas mask in the First World War.

Community, Commemoration and the First World War

Here’s an interesting piece by University of Nottingham engineer Mike Fay on the development of the gas mask in the First World War.

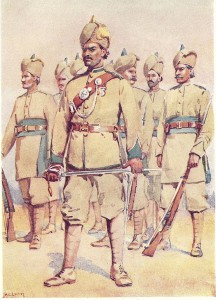

On Tuesday evening, I attended a commemorative event at the Imperial War Museum North. It had been organised to reflect on the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, which was the first major offensive to involve the British Indian Army.

Among the speakers at the event was Dr Santanu Das, of the English department at Kings College London. Dr Das, who is an expert in the culture and literature of the First World War, made the argument that while the First World War is often defined as the ‘clash of empires’, it could equally be defined as a watershed event in the history of cultural encounters in Europe.

Dr Das has been leading an international and interdisciplinary team of researchers and a number of cultural institutions across Europe to illuminate and examine this question during the centennial years of the war’s commemoration.

In this film we see how Dr Das has partnered with Imperial War Museum, London, In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, and the Museum of European Culture, Berlin to scour their (and many other) vast archives for letters, photographs, literary texts, sketches, artefacts, newspapers, and audio recordings. We see how all these sources are being brought together to be examined side-by-side, in order to piece together a fuller picture of the experience of the Indian troops and labourers, and the Europeans who they came into contact with.

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle was the first of the British spring offensives in 1915, when the Allied commanders were keen to escape the static conditions that had emerged and break through the German lines. They had planned simultaneous French and British attacks but when the British commander, Sir John French, requested reinforcements he was given territorials rather than regulars. This, and a sense that they were already over committed, prompted the French commander to call off his troops’ involvement, leaving the British on their own. Sir John decided to press on in any case (partly to impress the French following British failures to take ground in December 1914) and announced that the attack would take place at the ruined village of Neuve Chapelle in the Artois region of northern France and that Sir Douglas Haig would lead troops from the First Army (the IV Corps and the Indian Corps) in an effort to break through at Neuve Chapelle and capture the village of Aubers.

The German lines at Neuve Chapelle formed a salient, upon which Haig intended to converge his troops, the IV Corps (commanded by Lt. Gen Sir Henry Rawlinson) on one side, the Meerut and Lahore Divisions of the Indian Corps (commanded by Lt. Gen Sir James Willcocks) on the other. It would also be one of the first examples of the use of air power in warfare, with eighty-five aircraft conducting aerial reconnaissance, photography and cartography to aid the artillery bombardment.

On the morning of the 10th March 1915, following a thirty-five minute bombardment from hundreds of guns, the infantry launched their attack. A further barrage of artillery fire was committed behind the German trenches to prevent reinforcements from joining after the British attack. Sepoys of the Garhwal Brigade rushed across no-mans-land to seize Neuve Chapelle, taking 200 German soldiers prisoner. The village itself being taken less than an hour after the start of the assault and five of the eight assault battalions achieved their objectives with minimal losses. Many battalions were almost unscathed. In some areas the fighting was hand-to-hand. In the initial phase of the attack, everything seemed to be going in the British favour.

However, the commanders were unable to secure the breaches they had made in the German lines and were hampered by poor communications and the loss of field commanders, leaving poorly-briefed NCOs in charge of some units. Further progress and made the remaining push difficult and uneven. In particular, the northern sector, closest to Aubers itself, had managed to escape the British bombardment and the German lines remained intact. Every one of the thousand troops that advanced towards it was killed. Two German machine guns managed to kill hundreds of soldiers of the 2nd Scottish Rifles and the 2nd Middlesex, while other British troops lost their way in the confusion. Poor communication meant that the artillery couldn’t be informed of the situation in the front and were unable to respond, leaving the advancing troops to the mercy of the German guns. The battle went on for several days. On the fourth day, many of the surviving troops had to be roused ‘by force’ from sleep, a task made all the more difficult because they lay among corpses, indistinguishable at first glance from the sleepers.

Several problems emerged from the battle. The push took the infantry further away from their supply lines, isolating them and pushing the Germans further into their own territory. The more the British pushed, the worse they found things and, in terms of supply, the better things were for the Germans. Crucially, the push towards German lines took the British away from their lines of communication. They could lay telephone cables as they went, but these were easily cut by bombardment. Pigeons, flags and runners were ineffective and easily cut down. Relaying information to command, five miles behind the front, and back again to the advancing troops took eight or nine hours, meaning that effective, fluid commands were impossible. In addition, the men who led the attack were exhausted by the time they got to the German lines, making follow-throughs difficult. Reinforcements were difficult to supply, not least because of the poor communications.

The Outcome

A small salient, 2,000 yards wide by 1,200 yards deep had been taken and 1,200 German soldiers captured. 40,000 Allied troops took part during the battle and suffered 7,000 British and 4,200 Indian casualties. Similar losses were suffered by the Germans, setting the pattern for the slow, attritional nature of trench warfare.

Ten Victoria Crosses were awarded for conspicuous bravery in the battler. Among the recipients was Gabar Singh Negi of the 2nd/39th Gharwal Rifles. His entry in the London Gazette reads: For most conspicuous bravery on 10 March, 1915, at Neuve Chapelle. During our attack on the German position he was one of a bayonet party with bombs who entered their [the German] main trench, and was the first man to go round each traverse, driving back the enemy until they were eventually forced to surrender. He was killed during this engagement’. His name is among those recorded on the memorial at Neuve Chapelle. He was nineteen.

The Aftermath

Had the aim of the battle simple been to restore the British reputation in the eyes of the French, it would be considered a success. Perhaps even more coldly, the experience exposed the British commanders to some of the realities of trench warfare, giving them information that they could use in the development of new strategies and tactics. Reviewing the battle in his despatch to the Secretary of State for War, Sir John French attributed the success to ‘the magnificent bearing and indomitable courage[of] the troops of the 4th and Indian Corps’. Willcocks, who had served for many years in India and could speak several Indian languages, wrote that the Garhwalis ‘suddenly sprang into the very front rank of our best fighting men’. However, the impact of the losses took its toll, breaking up long-established units and, in some cases, killing officers who had worked with Indian troops and who knew and understood them, and leaving them to the care of men to whom the Indians were alien. In proportional terms, the Meerut Division lost 19 percent of its Indian soldiers d 27 percent of its British officers, while, with 575 casualties, the 47 Sikhs lost 80 percent of their fighting strength. These losses meant that, although not the last time that Indian troops would see action, Neuve Chapelle would be the last time that they were used as a striking force. It set the template for much of what was to follow. General Charteris wrote of the experience ‘I am afraid that England will have to accustom herself to far greater losses than those of Neuve Chapelle before we finally crush the German Army’.

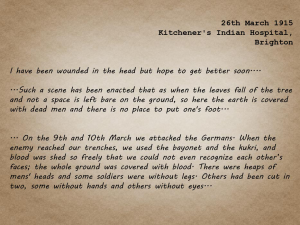

The personal impact of the battle was recorded by the survivors in letters home. The historian David Ommissi has collected some of the letters sent by Indian soldiers. Their comments testify to the almost indescribable bloodshed:

The Memorial

The memorial at Neuve Chapelle was erected by the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) in 1927. It is especially dedicated to the Indian soldiers who died in the battle and was designed with Indian culture and architecture in mind.

Now this looks like an interesting project. The Nottingham Radical History Group have used their long-standing experience of investigating and remembering radical moments from history to examine the cases of the 103 Sherwood Foresters who were sentenced to death or sentenced on mutiny charges during the First World War.

The project was deliberately chosen because of the high profile nature of the centenary. The group’s researchers soon realised the scale of their task and that their investigations would require them to familiarise themselves with the often arcane legal and organisational landscape of the military.

They have documented their approach in a brilliantly detailed initial pamphlet, which covers their work and the pattern of their investigations. It’s a fascinating example of the historical process and is written in an engaging and, at times, necessarily angry manner with footnotes that are as lively as they are informative.

The second in the series of pamphlets is also available. This begins the case study approach that the group has selected and focuses on the story of Private W. Harvey, who was sentenced to death for desertion in February 2015 (a sentence later commuted to two years’ hard labour).

As with the best works of history, this core story expands to examine the situation and context that surrounds it. Consequently, the pamphlet includes material on the lives that the soldiers left behind when they went to war and the experiences that the regiment offered once they had done so.

More information, and copies of both pamphlets, can be found on the People’s Histreh site

Movie portrayals of warfare can be very powerful, even when the war is not the central focus. Michael looks at an example from the 1990s

William Boyd’s 1999 film The Trench depicts a fusilier section during the 48 hours leading to the start of the Battle of the Somme.

The soldiers’ accents suggest a group drawn from different parts of the country, apparently in pairs with shared peacetime backgrounds. The putative lead, the Lancastrian Private Billy MacFarlane (Paul Nicholls) is partnered with his brother Eddie (Tam Williams) while a private dispute emerges on the part of the two Glaswegian soldiers over the issue of one’s clandestine engagement to a girl of their shared acquaintance. Lance Corporal Victor Dell (Danny Dyer) is a Cockney and Privates Ambrose (Ciaran McMenamin) and Rookwood (Cillian Murphy) Irishmen. Fusilier Colin Daventry (James D’Arcy) is evidently of a higher social class than his comrades and the likely beneficiary of a grammar school education (he has at least a smattering of German and has to pointedly moderate his latinate vocabulary to make himself understood even by his fellow Anglophones). He is, nevertheless socially inferior to the naive section commander, Second Lieutenant Ellis Harte (Julian Rhind-Tutt) who numbs his sense of being out of his depth with repeated slugs of whisky and private deferrals to his Sergeant, Telford Winter (Daniel Craig), the sole professional soldier in the unit.

The film’s action is almost entirely contained within the titular trench, creating an intentionally claustrophobic atmosphere that recalls a stage production. The young cast, mostly drawn from recent graduates of drama school is a reminder that the men who populated the trenches would, in other circumstances, be regarded as boys, a point emphasised by their scripted eagerness to participate in demonstrations of petty bravado, earning one lad a ‘blighty’ or in acts of barrack-room possessiveness over contraband photographs of nude girls.

Indeed, it is this matey comradeship (that includes minor rivalries) that is most impressive about this film. Take away the scenery and the uniforms and these lads could really be anywhere. Anywhere that raising your head too high might get you shot, that is. The effect of the scripting and the, let’s be honest, less than perfect nature of the performances (the young leads have all developed their acting skills since this film was made), lends The Trench a human quality that reminds us that the young men who fought in the real trenches were young, inexperience, scared and human.

The Christmas Truces are among the most celebrated events of the First World War. But what did they mean to the men who observed them?

As we have discussed before, the question of the Christmas Truces on the Western Front in 1914 is a vexed one. Although truces and ‘fraternisation’ are a matter of historical fact, they have been mythologised and turned intro material for ceremony, advertising and jokes. It’s easy to see why. The truces, symbolic of common humanity amid chaos and destruction, make for stories that are at once heartwarming and heartbreaking. But can they be more than that? It is to be hoped that they can and that this compelling phenomenon might prompt people to question the nature of war in general and this war in particular.

The truces certainly prompted questions back in 1914 and gave its participants cause to question what they were doing in the trenches, what their opposite numbers were doing and what they had both been told.

One of the highlights of the BBC’s Great War interviews, conducted in the early 1960s in advance of the half-centenary, is the series of anecdotes by Henry Williamson, who was in 1914, serving at the rank of Private in the London Regiment. At Christmastime 1914, he and his comrades were sent into no man’s land to hammer in some stakes to secure a key position. They were fifty yards from the German lines and, fearful of machine gun fire, began their sortie by crawling across the frozen ground. As time went on, they noticed that no gun fire came and they could walk freely on two legs, laughing and talking. ‘And then’, according to Henry ‘about eleven o’clock, I saw a Christmas tree going up on the German trenches. And there was a light’.

http://youtu.be/dUA8DSkSmBE?t=54m44s

The British soldiers approached the barbed wire which had been strung with empty bully beef tins so that it would rattle if a man drew near. Very soon they were exchanging gifts with the Germans. Smoking, talking and shaking hands, they swapped addresses so that we could write to one another after the war. And then they stopped to bury their dead.

The Germans used ration box wood to create makeshift memorials for their fallen comrades and offered a few words. ‘Für das Vaterland und Freiheit’, [For the Fatherland and freedom]. Williamson stopped him there. ‘How can you be fighting for freedom?’ he asked. ‘You started the war and we are fighting for freedom’.

‘Excuse me, English comrade’, replied the German. ‘But we are fighting for freedom’.

‘And here, you’ve put “Hier ruht in Gott” [Here rest in God]. ‘Yes,’ said the German,’ God in on our side’

‘But he is on our side’ replied Williamson.

That was, according to Williamson, a tremendous shock. ‘Here were these chaps, who were like ourselves, whom we liked and who felt about the war as we did, who said would be over soon because they [the Germans] would win in Russia and we said no, the Russian steamroller is going to win in Russia’

‘Well, English comrade’, replied the German ‘do not let us quarrel on Christmas Day.’

And quarrel they did not. Very soon, of course, both sides received stern orders to cease their fraternising and get back to their own trenches. But when the German machine guns resumed their fusillade, they were fired deliberately high and the British were advised to keep under cover in case ‘regrettable accidents’ happened. The truce, however, was over.

Henry William Williamson 1st December 1895-13th August 1977

Merry Christmas everyone.

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

It seems unlikely, given the state of no-man’s-land by December 1914, that anything like an organised football match took place during the Christmas truces. However, these spontaneous and cautious gestures did foster a handful of activities that may well have included a kick-about with a ball. It was then, as it is now, part of a universal language that demonstrates a similarity of outlook and reminds us that some things, class, fear, desire, football, remain the same no matter which direction your trench faces.

The existence of the Football Battalions, and the stories of professional players in the trenches offers a link to the past too. Young fans in 2014 can be encouraged to investigate the war by being reminded that, had they lived a century ago, the players they cheer on may well have ended up alongside them in uniform.

This is perhaps the thinking behind the Football Remembers project, run by the British Council, FA, Football League and Premier League. Starting on the 6th December, Football Remembers will encourage avid young historians and the footballing community to take part in a mass-participation event.

The scheme invites people to play a game of football, take pictures and share them via twitter with the hashtag #FootballRemembers. Any match of any size can be uploaded, from school to Sunday league fixtures, five-a-side matches to kick-abouts in the back garden. Teams in the Premier League, the Championship and FA Cup Second Round will also pose for group photographs before matches and will display them alongside these submitted pictures, as well as on a dedicated website.

In addition, the Premier League will hold a special edition of its annual Christmas Truce international tournament in Ypres, which it has staged for U12 footballers every year since 2011.

Special educational resources are available here and here to help with the planning of matches and, most importantly, for learning about the events of Christmas 1914.

In advance of giving an introduction to the film, Nigel Hunt explains what All Quiet on the Western Front means to him

When I was a second year (modern year 8) at my local comprehensive school, I went to the book store with the teacher, saw a pile of copies of All Quiet on the Western Front and, as I had read the book the year before at the age of 11, I asked the teacher if we could study it in class. She said we were ‘too young’ for such a book. This had two profound effects on me. First, I more or less gave up on school as a place I could gain a decent education. Second, I continued to read the book virtually every year for at least the next decade. It was, and is, my favourite book about war.

One of the great anti-war war novels of all time, Erich Maria Remarque’s book about the First World War came out in 1929, a decade after the end of the war. It was quickly translated into many languages, including English (the Wheen translation remains the best), and it has remained popular ever since. While the book is about the experiences of Germans on the Western Front, and the action takes place throughout the war, Remarque himself spent about a month at the front, before being wounded and spending the rest of the war in hospital. His vivid description of war is memorable; his characters real, his dialogue dramatic. The book was so popular, and so anti-war, that it was banned during the Third Reich. Remarque himself had to leave Germany, first to Switzerland, and then to build a successful career in the USA. Remarque was from the Rhineland, a descendant of French people who escaped the revolution. He reverted from Remark to Remarque as it was the original spelling, and took Maria from his mother’s name.

The first – and in my view best – film of the book came out in 1930. It was filmed in the USA and used hundreds of actors, many of whom were ex-German soldiers who had moved to the USA after the war. They were used as advisers for the action sequences and for the uniforms.

The director, Lewis Milestone, was a Moldovan, raised in Ukraine and educated in Belgium and Berlin. He was in the US army from 1917 as a signaller, obtained US citizenship after the war, and went to Hollywood. He quickly worked his way up the ranks and directed his first film in 1925, Seven Sinners. He won an academy award in 1927 for Two Arabian Nights, and won a second one for All Quiet on the Western Front (It also got best picture).

The main character, Paul Baumer, was played by Lew Ayres, who was so affected by the film that he became a conscientious objector in the Second World War, serving as a medic in action in South East Asia.

Nigel Hunt will give an introduction to All Quiet on the Western Front at a free public screening of the film at Broadway Nottingham on Monday 8th December at 6pm. Tickets are free and available from the venue on the day.

The Christmas Truce is one of the most enduring images of the First World War. Does this make it fair game for advertisers? Michael Noble takes a look

The decision by Sainsbury’s to use the imagery of the 1914 Christmas truce in their festive advertising campaign has proved controversial. In some quarters, the advert has been well received: the Metro described it as ‘emotional and t ouching without being sentimental‘ while the Telegraph called it ‘heart-warming‘. Others have questioned its appropriateness. Writing for the Guardian’s Comment is Free, Ally Fogg conceded that it was very well made but said that using the war for commercial purposes left him ‘unsettled, uncomfortable, even a touch nauseous‘. The advert has also been discussed by professional historians, such as the University of Birmingham’s Dr Jonathan Boff, who admits to ‘deep reservations‘ about the advert. Part of his concern is driven by a desire for historical accuracy:

ouching without being sentimental‘ while the Telegraph called it ‘heart-warming‘. Others have questioned its appropriateness. Writing for the Guardian’s Comment is Free, Ally Fogg conceded that it was very well made but said that using the war for commercial purposes left him ‘unsettled, uncomfortable, even a touch nauseous‘. The advert has also been discussed by professional historians, such as the University of Birmingham’s Dr Jonathan Boff, who admits to ‘deep reservations‘ about the advert. Part of his concern is driven by a desire for historical accuracy:

That some truces did occur is beyond doubt. That someone kicked an improvised ball about is highly likely. But that’s a long way 1) from saying there was a general truce and 2) from the sad and unpleasant fact that many or most of the truces which occurred were for the much more pragmatic and distasteful purpose of burying corpses. The need to respect the dead and prevent disease was much more pressing than goodwill and sharing chocolate.

He’s also concerned that, however well made the advert is, it cannot escape the charges of exploitation and that ‘by associating the truce so closely with goodwill and sharing [the advert] bends the past too far away from reality and to the advertiser’s ends’.

The debate will no doubt endure, at least until Christmas when the centenary of the truces, sporadic as they were, will be upon us.

In the meantime it’s worth looking at how the war was used by advertisers while it was still being fought. From its earliest days the war appeared in popular and commercial culture, which is understandable, given the scale of its impact. Consequently, the war appeared in the imagery of advertisements, both as a general backdrop and as the source of implied need that all advertising relies upon. Bran ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.

ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.

Other companies, whose association with the war may seem tenuous to us, claimed a solid and necessary link to the trenches. In 1918 Decca, the then manufacturers of a gramophone, ran an advert with the striking headline ‘The cussed Huns have got my gramophone’. The phrase emerged from a report in the Evening Standard in which British soldiers complained about the loss of their property to German raiding parties. Gramophones, which were amplified by vibration rather than electricity, were popular in dug-outs, given their application as a means to drown out the relentless noise of war.

Did Bovril, Oxo, Decca and the rest make any additional sales from their advertising? One would expect so. In poor taste? Our modern sensibilities would perhaps balk more at the use of the term ‘Hun’ than at the depiction of the war itself. Even the Sainsbury’s advert, if it is misjudged at all, is more so because it challenges a received myth about the spontaneous humanity than because it centres upon a century-old war. Certainly, other conflicts have been featured in advertising before.

Here, for example, is the Battle of Agincourt, used to promote BBC Rugby coverage:

And remember this? Carling being advertised by another, more recent, interaction between British and German forces:

Is the First World War sacred? Or is it that the idea of the truce occupies a certain place in the public mind and that using it for commercial gain is troubling?

Either way, it’s perhaps a good thing that it gets people talking about the war if, and only if, a through conversation can be had about what happened at Christmas 1914 and what it means to us today.

It has been estimated that by late 1914 fifty-five different nationalities were represented at the Western Front, creating a melting pot of identity, experience and language. The Centre for Hidden Histories’ resident linguist Dr Natalie Braber examines some of the inventive terms that the soldiers used to describe their comrades and enemies.

As a result of World War One, people came into contact with one another more than they otherwise would have and one of the effects of such contact is a change in language. This can be due to ‘invention’ of new words, or ‘borrowings’ from other languages. A very fruitful field for linguistic study is to examine how soldiers from countries are referred to. British soldiers were often referred to as ‘Tommy’ from Tommy Atkins, the name for the typical English soldier. This term dates back to 1815 and became immortalised in the Rudyard Kipling poem ‘Barrack Room Ballads’ published in 1892. This term was used throughout WW1 by both sides.

There were also names given to soldiers of other nationalities: Italians were referred to as ‘Macaroni’, Portuguese as ‘Pork and Cheese’, ‘Pork and Beans’ or ‘Tony’, Austrians as ‘Fritz’ and Turkish soldiers as ‘Jacko, Johnny Turk or Abdul’.

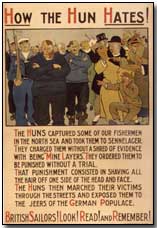

There are many different terms used for German soldiers. Reports of the ruthlessness of the German army in China in 1900 refer to the use of ‘Hun’ by the German emperor as a symbolic ideal of military force and so this name came to be applied in 1914, in particular when discussing atrocities. The terms ‘Hun’ and ‘Boche’ were also in use throughout the war. Boche is said to have derived from a slang French word ‘caboche’ meaning ‘rascal’. Other suggest the term ‘cabochon’ relates to ‘head’ and especially a big thick, head. It seems to have been used in the Paris underworld from about 1860, with the meaning of a disagreeable, troublesome fellow. By 1916 the term ‘Jerry’ was in general use. The first time it was used in the Daily Express it was explained ‘The ‘official’ Irish designation of the enemy’. This term seems to carry more connotations of weariness and familiarity than hate.

As well as names for other soldiers, the men on the front were inventing new words due to contact with other soldiers from other nationalities as well as other parts of the United Kingdom. ‘Clink’, originally a London word for prison became widely adopted by men from around the country. A writer to The Times in January 1915 proposed that ‘the majority of colloquialisms used by soldiers have a Cockney origin’. Given the number of British personnel stationed on French territory it is unsurprising that many French terms were picked up and adapted. The increased use of ‘souvenir’ in place of ‘keepsake’, and ‘morale’ in place of ‘moral’ can be dated to this period. Perhaps the term most widely-used by British soldiers was ‘narpoo’, used to mean ‘finished’, ‘lost’ or ‘broken’, deriving from the French il n’y a plus meaning ‘all gone’. Terms were adopted and adapted from almost all languages that were in use in the combat zones. From Hindi came ‘blighty’ (meaning ‘foreign’ so applied to British soldiers, and thus signifying ‘Britain’) and ‘khaki’ from an Urdu word for ‘dust’. From Russian came ‘spassiba’ (thanks), from Arabic came ‘buckshee’ (free), and from German achtung came ‘ack-dum’ (look out).