Here’s an interesting piece by University of Nottingham engineer Mike Fay on the development of the gas mask in the First World War.

Community, Commemoration and the First World War

Here’s an interesting piece by University of Nottingham engineer Mike Fay on the development of the gas mask in the First World War.

John Beckett recounts the story of Thomas Porteous Black, the Registrar of University College Nottingham, who fought at Gallipoli.

The commemoration on 25 April 2015 of the centenary of Gallipoli, reminds us that white British casualties were found in places other than the trenches of the Western Front. The conflict itself is often viewed as being about the Australian and New Zealand troops, who went into action in Europe for the first time. ‘The ordeal of courageous Anzac troops under the command of bungling British generals has become the stuff of legend’ according to The Times (25 April 2015). By contrast, Britain has not made a great deal of the campaign, which was seen as botched, primarily by Winston Churchill, who had seen it as a way of opening a new front in the Eastern Mediterranean. Britain sent a 75,000 strong Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, which included British, Irish, French, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. By August 1915 the situation was dire, with troops pinned down in a bloody stalemate, having failed to move further than three or four miles inland.

Among the casualties was Thomas Porteous Black. A native of Aberdeen, but brought up in Darlington, Black was killed at Suvla Bay on 9 August 1915, as the 9th Sherwood Foresters were ordered forward against Turkish lines near Hetman Char in the Dardanelles.

Black’s death had a particular impact on Nottingham University College because he held the position of Registrar, at that time the senior administrator of the institution. He had joined the College as a lecturer in Physics, and had been appointed Registrar in 1911. As an officer in the OTC (Officer Training Corps), he quickly became involved in the war effort, and when the war started he joined up as a Sherwood Forester. As with all of the young men who died, and who had some form of association with the College, his loss was reported to both Senate and Council and, as ever, letters of condolence were sent to his family. He is also named on the university’s war memorial in the Trent Building.

In Black’s case the College decided to go further and to create a scholarship fund ‘to be awarded for research and to bear his name’. A circular letter dated 20 November 1915 and signed by the College vice principal Frank Granger and by E Lawrence Manning, described as honorary secretaries and treasurers for the Black memorial award, recalled how, as registrar, he had ‘carried out duties of special responsibility with an energy, foresight and tact, which was of great value to the numerous students who entered the College during his term of office.’

The letter continued: ‘It is hoped to raise a sum of £300 with a view to establishing a scholarship to be awarded for research and to bear his name.’ More than £50 had already been donated, including £10 10s from Principal Heaton, and £5 5s from his wife. A concert was held on 25 March 1916 to raise money towards the Black Memorial Fund.

By that time the ill-fated campaign in the Dardanelles was over. The Commander-in-Chief, General Ian Hamilton was recalled in October, and an evacuation began in December, which ended on 9 January 1916.

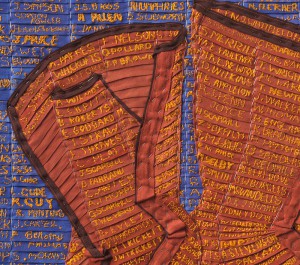

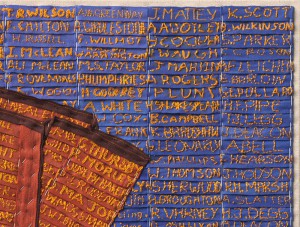

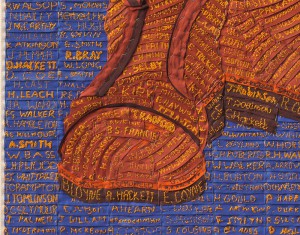

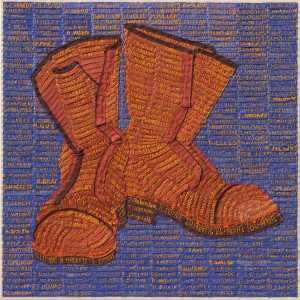

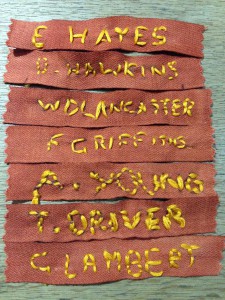

Many of you will recall the Military Boots project that we blogged about last October. The project, which was led by Nottinghamshire artist Joy Pitts, invited people to stitch names of soldiers from the First World War into strips of cotton, which she would arrange into a coherent image of a pair of military boots. The blog was one of our most popular and it was clear that Joy’s project attracted a lot of interest.

Many of you will recall the Military Boots project that we blogged about last October. The project, which was led by Nottinghamshire artist Joy Pitts, invited people to stitch names of soldiers from the First World War into strips of cotton, which she would arrange into a coherent image of a pair of military boots. The blog was one of our most popular and it was clear that Joy’s project attracted a lot of interest.

The project has now been completed and you can see some images of the finished piece below.

The artwork will be exhibited at Lace Market Gallery, 25 Stoney Street, Nottingham NG1 1LP from the 23rd April to the 13th May 2015. The gallery is open Monday to Friday, 10am-4pm term time only

Now this looks like an interesting project. The Nottingham Radical History Group have used their long-standing experience of investigating and remembering radical moments from history to examine the cases of the 103 Sherwood Foresters who were sentenced to death or sentenced on mutiny charges during the First World War.

The project was deliberately chosen because of the high profile nature of the centenary. The group’s researchers soon realised the scale of their task and that their investigations would require them to familiarise themselves with the often arcane legal and organisational landscape of the military.

They have documented their approach in a brilliantly detailed initial pamphlet, which covers their work and the pattern of their investigations. It’s a fascinating example of the historical process and is written in an engaging and, at times, necessarily angry manner with footnotes that are as lively as they are informative.

The second in the series of pamphlets is also available. This begins the case study approach that the group has selected and focuses on the story of Private W. Harvey, who was sentenced to death for desertion in February 2015 (a sentence later commuted to two years’ hard labour).

As with the best works of history, this core story expands to examine the situation and context that surrounds it. Consequently, the pamphlet includes material on the lives that the soldiers left behind when they went to war and the experiences that the regiment offered once they had done so.

More information, and copies of both pamphlets, can be found on the People’s Histreh site

Here at the Centre for Hidden Histories we spend a lot of our time talking about the roles that different faiths, nationalities and groups played in the First World War. This, we believe, is a valuable endeavour, but it still doesn’t tell the whole story. Perhaps nothing ever will, but to even approach a comprehensive understanding of the war, there is another group to consider. The people of Germany.

For reasons too obvious to list, the relationship between Britain and Germany was forever changed by the war. This had an impact at the state, community and individual levels and traces of this impact can still be felt today.

On the 23rd March we will be hosting a discussion event to explore these issues and to develop project ideas to investigate them further. We invite community groups to share project ideas for investigating this relationship and the different meanings that the war had, and continues to have, in the two countries.

Discussion topics are likely to include:

This is not an exhaustive list and we’d be delighted to consider any topic that falls within our theme of the relationship between British and German people during and since the First World War.

The event is free, but places are limited. Tickets can be booked here.

Britain, Germany and the First World War Discussion Event

23rd March 2015 4pm-7pm

University of Nottingham

Chilwell resident Michael Noble looks at a dark event from the district’s wartime past…

It wasn’t over by Christmas. The extended duration of the war wasn’t entirely unexpected (eagle-eyed members of Kitchener’s New Army will have spotted that they’d signed up for ‘three years or until the war was over’) but it wasn’t necessarily planned for either. Several months of heavy shelling, with hungry guns well-supplied by rail, led to the rapid depletion of high explosive shells by early 1915. The resultant ‘shell crisis’ was a notable scandal in many combatant countries and in Britain led to political turmoil that saw the creation of a coalition government and the founding of a Ministry for Munitions, led by David Lloyd George.

Existing arms factories were brought under tighter official control and several new installations were created, among them No. 6 Filling Factory at Chilwell in Nottinghamshire. The dangerous duty of the filling factories was to take the explosive chemical compounds and add them to the empty shells that had been made for the purpose. The Chilwell factory, like many such places, was staffed largely by women, nicknamed ‘munitionettes’ or ‘canaries’, owing to their yellow complexions, caused by their absorption of poisonous chemicals.

The Chilwell factory was efficient (evidence suggests that Chetwynd was a hard taskmaster) and filled over nineteen million shells during the war. It was, nevertheless, dangerous work. Factory staff wore rubber boots in an effort to avoid making sparks that could set off a deadly conflagration. Rings and shoelaces were banned. You can never be too careful. Sadly, you can still never be careful enough. On the 1st July 1918 a massive explosion occurred, destroying much of the installation, killing 134 people and injuring 250 more.

The disaster had an understandable impact on those who survived it. It did not, however, break their spirit or commitment and the factory continued to produce shells, achieving its highest weekly output within a month of the explosion. The event was subjected to a thorough investigation and, while Chetwynd suspected sabotage, this could not be proven.

Of course, the factory did eventually cease production several months later when the Armistice was declared. The site is now owned by the Ministry of Defence and is home to the Chetwynd Barracks. a memorial to those who died in the explosion was erected in the grounds and still stands today. A plaque offers some details of the events of wartime, but like the factory staff themselves, remains focused on the output of shells:

Erected to the memory of those men and women who lost their lives by explosions at the National Shell Filling Factory Chilwell 1916 – 1918

Principal historical facts of the factory

First sod turned 13th September 1915

First shell filled 8th January 1916

Number of shells filled within one year of cutting the first sod 1,260,000

Total shells filled 19,359,000 representing 50.8% of the total output of high explosive shell both lyddite and amatol 60pd to 15inch produced in Great Britain during the war

Total tonnage of explosive used 121,360 tons

Total weight of filled shell 1,100,000 tons

If you’d like to find out more about the Chilwell Filling Factory, you can hear an audio recording of Emily May Spinks, recalling her time as a teenage employee and her memories of the explosion. A 30 minute documentary, The Killing Factories is also currently available on the BBC iPlayer.

A Nottinghamshire artist has found a unique way of remembering those who served, and those who continu e to do so. Michael Noble takes a look.

e to do so. Michael Noble takes a look.

Joy Pitts is a multiple award-winning contemporary artist based in Nottinghamshire. She works primarily with garments, which she sees as expressive of our individual identity and way of life. Her work assembles these individual identities into a shared whole that represents the collection of individualities that we call society.

This concept has a natural mirror in the idea of war memorials that place individual names in a shared space. One of Joy’s current projects reflects this by seeking to gather individually-sewn names of servicemen and women and present them as a single art work on canvas that will depict a pair of military boots. The Military Boots project is a collaborative effort being undertaken as part of Nottinghamshire’s Trent to Trenches programme.

Joy would like to invite you to contribute to this project by stitching the name of those in your family past or present who have served or are serving in the Armed Forces onto a strip of cotton tape for her to add to the art work. She will provide the materials, you just need to provide the names and a little bit of your time.

Joy says ‘during World War One it was common for both men and women to sew; repairing clothing at home and in the trenches, embroidering messages to send to loved ones and sewing bandages. This project recalls these activities and invites you to make your own hand made acknowledgement to those who serve.’

If you are interested in taking part, you can contact Joy directly here to request a stitch pack.

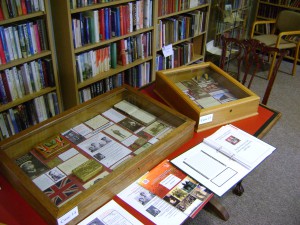

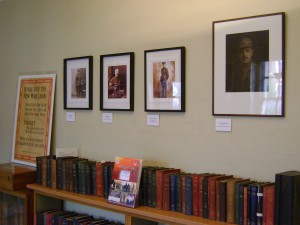

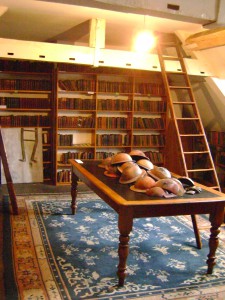

The Bromley House Library is holding a series of events to commemorate the war. Michael Noble takes a look at what’s on.

The Bromley House Library has served the people of Nottingham for almost two hundred years and is, at the start of the twenty-first century, one of the few remaining subscription libraries in the country. Its appeal lies partly in its collection of around 40,000 books and also in its pleasant atmosphere, described as ‘tranquil and unstuffy’ atmosphere. Founded in 1816, the library has been situated since 1822 in Bromley House, a Georgian townhouse that is now Grade II* listed. Access to the library is usually limited to paying subscribers but it is opening its doors this autumn and inviting the public to pay a visit to see a specially-commission exhibition of First World War artefacts and to hear a range of guest speakers.

The exhibition, which has been generously supported by the Lady Hind Trust, has been mounted as part of Nottingham’s Trent to Trenches programme. It consists of items that have been kindly loaned by the library’s members in an effort to tell the ‘stories’ behind their families’ experience of the Great War.This creates a natural focus on the war as it was experienced by Nottingham people. This personal element is made all the more poignant by the setting of cherished objects alongside beautiful photographic images of their owners, some of whom gave their lives in the conflict. A modern interpretation of the war is provided by local artist Janet Wilmot, whose works have been displayed to accompany the historical material.

The exhibition is displayed in the Bromley House Gallery and in the main reading rooms, and is open to the public every Wednesday from 10.30am – 4pm In addition, the library has a diverse programme of subjects and speakers for Saturday lectures (£5.00 pp) and Wednesday lunchtime talks. The talks on Wednesdays are free but tickets need to be reserved in advance.

For further information about the programme and reserving tickets please contact geraldine.gray@bromleyhouse.org, or phone 0115 9473134, visit www.bromleyhouse.org or just pop in!

The First World War had an impact on many large institutions and the University College, Nottingham was no different. John Beckett looks at the role played by the college in preparing young men for warfare.

The impact of the First World War on University College, Nottingham, was profound. By its very nature, an institution concerned with higher education was likely to have a large number of young men on its books, both as students and staff, in the appropriate age range to join the armed forces. In addition, the formation of the Officer Training Corps (OTC) had encouraged the notion even in peace time, that educated young men should be considered as potential military leaders in the event of war.

In 1906 Lord Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, appointed a committee to look into the problems caused by shortages of officers in the military reserve The committee recommended the formation of what became known as the OTC with a senior division in the universities, and a junior division, now the Combined Cadet Force, in public schools. University College Nottingham OTC was formed on 27 April 1909, following a petition signed by 27 students who were no doubt imbued with the patriotic ethos which underpinned the OTC. The Commanding Officer, from the beginning and throughout the war, was Captain Samuel R.T. Trotman, M.A., F.R.I.C.

The war broke out in the middle of the College’s summer break, but within a few days it was announced that it would provide facilities for the training of a limited number of young men in the theoretical and practical subjects required by the syllabus of the OTC examination. Applications were sought from those who intended to apply for commissions in the Special Reserve or the Territorial Force. In other words the College would adapt to provide the training required by potential officers.

All male students were eligible to volunteer. They enrolled in the O.T.C. as cadets and undertook theoretical and practical military training alongside their college studies. The training involved instructional parades, exercises and field operations, musketry, annual training at camp, lessons in tactics, map reading and military engineering. Student Cadets who passed an examination were entitled to a commission in the Reserves, or Territorial Force. Trotman rapidly built up the numbers and by 1913 he had 106 cadets. We know from his remarks at the November 1912 prize giving that he was a firm believer in preparing for war. As the historian Robert Mellors noted of Trotman,

‘he had travelled in Germany, and seen the preparations, and arrived at the conclusion that War was intended; he thereupon resolved that he would do all that one man could towards saving his country, and he did it’.

Trotman, born at Frome, Somerset, in 1869, had been Science master at the Nottingham Boys High School, where he had trained the Cadet Corps. From 1893 he was Nottingham City and Public Analyst, and having agreed to take on the OTC he found himself with two demanding tasks when the war broke out. To do them both, he rose at 4 a.m. to spend three hours in his laboratory before breakfast, he then went to Bulwell Hall to train recruits from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and frequently returned to his laboratory in the evening.

Initially the corps had its emergency headquarters at Trotman’s house in Lucknow Drive, Mapperley. This was then moved for a time to Bilbie Street, and each day the contingent marched out to Bulwell Common for training. Eventually Nottingham Corporation placed Bulwell Hall at its disposal, and those cadets who did not live in the vicinity were billeted there, under the personal supervision of Trotman and his wife who for some time lived in the hall and cared for their adopted family. Fortunately, Trotman’s wife appears to have been as committed to the cause as he was, and provided ‘motherly aid’ to the boys living at Bulwell Hall.

In total 103 Nottingham cadets had been gazetted to commissions by November 1914. Many of them, Trotman recalled, had enlisted ‘and in most cases obtained commissions very quickly’. By then one staff member, Captain Frederick Forster, and four senior officers with attachments to the unit, Major Charles Pack-Beresford, Major William Christie, Major Nigel Lysons and Lt Col Walter Loring, had fallen. On 24 November 1914 it was agreed to place a Roll of Honour in a prominent place for members of staff and students who had joined up.

These arrangements were formalised in December 1914 when a Department of Military Science was set up to teach the skills that officers would need in the war. Trotman was commissioned to prepare a course of study for students suitable to those studying for degrees and those seeking commissions. He told Council in December 1914 that Military Science would occupy three hours of lectures each week for map reading, military engineering, and practical work such as the ability to handle a company of infantry, advanced military science, special courses to meet national emergencies, and courses for those unable to undertake military duties. Trotman was given the position of Honorary Director of the department. Certificates of proficiency were granted, and special advantages were conferred upon the holders of the certificates. Various facilities were provided for shooting practice, including Miniature Ranges – Carrington Range (open air) 25 and 50 yards, and the High School Range 25 Yards – and the full range at Trent College:

‘A qualified Sergeant-Instructor is appointed, and every facility is offered to a cadet to become efficient. Uniform, equipment and ammunition are provided, so that membership entails no expense. All enquiries should be addressed to Capt S.R. Trotman, University College, Nottingham.’

Within a year ninety students had enrolled for the course, and by the end of 1915 365 students were attending classes in the Department of Military Science.

Special courses of lectures were delivered to officers, NCOs, and men of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Regiment and the RFA, stationed in Nottingham. Miss Hutchinson lectured on ‘The Health of the Soldier and Care of the Wounded’. Professor Kipping gave lectures on ‘Map Reading’, Mr A.H. Simpson on ‘Aids to Military Night Work’, Mr A Levi on ’The Care of the Horse’, and Professor Robinson on ‘The Motor Car in Battle’ – an indication of the overlap between old and new which marked the war.By the end of 1915, 748 former students and members of the OTC had joined the armed forces. Military Science was open to all students able to handle a company of infantry, and courses were on offer for those unable to undertake military duties, and by the end of 1915 special classes had been introduced for men wishing to obtain speedy commissions in the army and attended by 365 students.

In September 1915 members of the Citizens’ Army requested to be allowed to attend the evening classes on military science, but it was left to Trotman to decide whether or not this was feasible. The result was that lectures and practical instruction for officers of the Citizen Army were available from here until the end of the war. Lectures offered to members of the Citizen Army included Captain Trotman on ‘Tactics’, Professor Kipping on ‘Musketry’, and 2nd Lieut Mee on ‘Map Reading’.

Trotman’s work altered when in 1916 the government introduced conscription. A part-time military science course for boys under military age was introduced, together with a full-time military science course for boys approaching military age, and numerous other courses. Trotman later recalled: ‘we trained large numbers of “attested recruits” until their turn came to join up’, in other words they trained potential officers who enlisted when they were old enough: ‘We held classes for this purpose also in Mansfield both on weekdays and Sundays.’ He added that ‘for a considerable time the only rifles in Nottingham were those belonging to the O.T.C. and the rifle instructor which we were always willing to give to the Citizen Army and others was much appreciated’. Students of the Elementary Training Department who had joined the army under conscription were to have their entrance fee returned to them and advised that should they wish to return after the war they would be admitted for a further two terms without payment.

The form of education on offer changed again in 1917 when a new scheme was introduced allowing students wishing to train for commissions to attend instruction in the department of Military Science every morning, and Monday and Thursday afternoons additionally, and special classes on the other three afternoons. In October 1917 students doing Military Science were expected to attend Bulwell Hall on a Thursday and Saturday, and to wear uniform.

By 1918, 1,632 cadets had passed into the Army through the University College. They won five DSOs, 91 MCs, fourteen with bars, and several Croix de Guerre and other decorations, besides nearly 50 mentions in dispatches. More than 500 were wounded and 229 died. Some outstanding young officers graduated through the Nottingham OTC. Philip Johnson ‘personally brought back six machine guns’, while his sister Winifred left elementary school teaching in Nottingham to nurse on the Western Front. Frank Hind (19) died attempting the rescue of a comrade under heavy fire. Eustace Cattle ‘led a bombing attack under very difficult circumstances … crossing in the open to do so under close and heavy fire from enemy snipers’. William McClelland was described as ‘one of the bravest men in the line; Harry Beedham led a bayonet charge at Cambrai; Charles Vigors ‘showed great course and determination’ in repulsing an enemy attack in Salonika.

When, eventually, the war ended, there were numerous pieces to pick up: students who returned to complete their studies, frequently mixing with young men and women who had not played any direct role in the war; and new challenges in terms of the curriculum, arising from concerns which had arisen about Britain’s overall educational attainment.

Trent to Trenches is the official commemorative project of Nottingham City and County. Michael Noble paid a visit to see how the first ‘global war’ remained steadfastly local.

Whether by sending its young men off to fight on land, sea and air, by contributing materially to the war effort or by banding together as the costs of the conflict grew, every corner of the country was affected in some way by the First World War. The local impact of the war remains a powerful one and is central to the Trent to Trenches project in Nottingham.

sending its young men off to fight on land, sea and air, by contributing materially to the war effort or by banding together as the costs of the conflict grew, every corner of the country was affected in some way by the First World War. The local impact of the war remains a powerful one and is central to the Trent to Trenches project in Nottingham.

The central exhibition, based at Nottingham Castle, weaves the local seamlessly through a series of objects and stories that nonetheless reflect the global nature of the war. A detailed timeline, painted onto the walls, matches events in Nottinghamshire with those that took place around the world. As visitors progress through the displays (a skilful blend of the chronological and the thematic) materials such as uniforms, letters, diaries and photographs, many of which were kindly loaned by local people, emphasise the ‘Nottingham-ness’ of the war. A lace panel, reflective of one of the town’s traditional trades, portrays British, French and Belgian soldiers as they would have appeared at the start of the war. A huge Union Jack dominates one wall. Its origin? HMS Nottingham, the light cruiser that was sunk by a U-boat in 1916.

The Nottingham had recently taken part in the Battle of Jutland, which was not the only major engagement that had a local angle. During the Battle of the Somme, the Sherwood Foresters were deployed at Gommecourt, towards the northern end of the line. Their role was a diversionary one, intended to draw German attention away from the main assault further south. The exhibition tells the story through an emotionally affecting film which cleverly uses local information to make it familiar: the territorial gain was ‘the distance from Nottingham Castle to Radcliffe-on-Trent’. Doing that in the East Midlands would cost you about two hours on foot. In France on the 1st July 1916 it cost the Sherwood Foresters 424 officers and men.

Further familiarity is found in the personal. You can see Nottingham schoolboy Raymond Pegg’s beautifully illustrated diary in which he commented on the development of the war with the eager pupil’s eye for details of flags and military equipment. The diary, in Raymond’s well-drilled handwriting, is accompanied by photographs of the lad as he would have appeared in between making entries and is a fascinating insight into the mental world of a young civilian at the time.

Flying Ace Albert Ball, a local and national hero, is given a section to himself, with photographs, clothing and other items of interest including his personal weapons. Ball, the son of a wealthy Nottingham businessman, was born on Lenton Boulevard in 1896 and fostered an early interest in engineering which led him to pursue a wartime career in the air. As with so many early airmen, this career was a painfully short one, which ended in 1917 in a crash at Douai in France, but it was a successful one and Ball was the most successful British airman at the time of his death. The ‘Wonder-Boy of the Flying Corps’, his exploits were celebrated internationally, and even acknowledged by Manfred von Richthoffen, the ‘Red Baron’, who described him as ‘the best English flying man’. For all this celebrity, the most resonant aspect of the Ball exhibit is the local and personal -his signature on his flying certificate, the images of his family or the photograph of him as a toddler at home in Nottingham, a local lad from the very beginning.

The Trent to Trenches exhibition is at Nottingham castle from Saturday 26th July – Sunday 16th November 2014.