In advance of giving an introduction to the film, Nigel Hunt explains what All Quiet on the Western Front means to him

When I was a second year (modern year 8) at my local comprehensive school, I went to the book store with the teacher, saw a pile of copies of All Quiet on the Western Front and, as I had read the book the year before at the age of 11, I asked the teacher if we could study it in class. She said we were ‘too young’ for such a book. This had two profound effects on me. First, I more or less gave up on school as a place I could gain a decent education. Second, I continued to read the book virtually every year for at least the next decade. It was, and is, my favourite book about war.

One of the great anti-war war novels of all time, Erich Maria Remarque’s book about the First World War came out in 1929, a decade after the end of the war. It was quickly translated into many languages, including English (the Wheen translation remains the best), and it has remained popular ever since. While the book is about the experiences of Germans on the Western Front, and the action takes place throughout the war, Remarque himself spent about a month at the front, before being wounded and spending the rest of the war in hospital. His vivid description of war is memorable; his characters real, his dialogue dramatic. The book was so popular, and so anti-war, that it was banned during the Third Reich. Remarque himself had to leave Germany, first to Switzerland, and then to build a successful career in the USA. Remarque was from the Rhineland, a descendant of French people who escaped the revolution. He reverted from Remark to Remarque as it was the original spelling, and took Maria from his mother’s name.

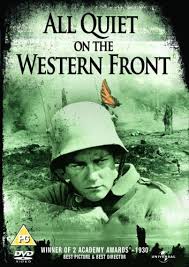

The first – and in my view best – film of the book came out in 1930. It was filmed in the USA and used hundreds of actors, many of whom were ex-German soldiers who had moved to the USA after the war. They were used as advisers for the action sequences and for the uniforms.

The director, Lewis Milestone, was a Moldovan, raised in Ukraine and educated in Belgium and Berlin. He was in the US army from 1917 as a signaller, obtained US citizenship after the war, and went to Hollywood. He quickly worked his way up the ranks and directed his first film in 1925, Seven Sinners. He won an academy award in 1927 for Two Arabian Nights, and won a second one for All Quiet on the Western Front (It also got best picture).

The main character, Paul Baumer, was played by Lew Ayres, who was so affected by the film that he became a conscientious objector in the Second World War, serving as a medic in action in South East Asia.

Nigel Hunt will give an introduction to All Quiet on the Western Front at a free public screening of the film at Broadway Nottingham on Monday 8th December at 6pm. Tickets are free and available from the venue on the day.