The Centre for Hidden Histories is proud to present a public talk on the subject of British Public Parks and the First World War. Professor Paul Elliott, of the University of Derby, will give the talk at Derby Quad on Wednesday 27th May at 7pm. Here, Professor Elliott introduces some of the themes that he will cover in his talk.

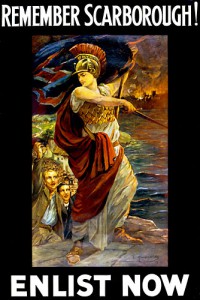

On 16 December 1914 German shells thudded into Scarborough from the sea, aimed at a Naval Wireless Station at the top of Falsgrave Park. In all, the bombardment killed 17 people including a 14 month old child who had been in Westbourne Park. Apart from this highly unusual episode in the home front context, public parks were rarely, of course, the targets of German bombs, although perhaps they ought to have been, as they were playing their role in the war effort.

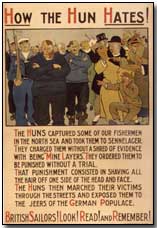

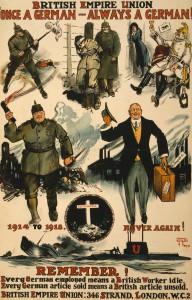

Public reaction to the conflict changed over the course of the war, with propaganda and rumour fostering patriotism and hatred of the enemy whilst the ethic of volunteerism and the rhetoric of sacrifice were prominent in debates over where the burdens of war should fall and documented in public discourse, as well as the influence of religious ideas. As the war drew to a climax, tensions about the distribution of sacrifices threatened to tear society apart, whilst victory and the processes of commemoration helped create a fiction of a society united in grief.

This talk will argue that public parks were caught up in some of these reactions and ambiguities, and were utilised both in support of the war effort in various ways and also sometimes as places where resistance to the war and its consequences occurred. The recruitment of hundreds of thousands of men for the armed forces, food shortages and rationing, the assumption of male work roles by numerous women, all impacted upon urban parks and green spaces. As we shall see, public parks in Derby and other places were requisitioned for various purposes including military (such as anti- Zeppelin and aircraft guns), defensive, governmental, medical and for food production, particularly after the Defence of the Realm Act or (DORA) was passed. They also played an important role in maintaining morale when some other forms of recreation were curtailed such as organised sports like football and rugby. At the same time, parks were places where civilian and military populations on leave or recuperating could temporarily escape from some of the demands of war and even resist authority. On occasion they served as venues for anti-war and pacifist meetings and demonstrations too.

This talk will argue that public parks were caught up in some of these reactions and ambiguities, and were utilised both in support of the war effort in various ways and also sometimes as places where resistance to the war and its consequences occurred. The recruitment of hundreds of thousands of men for the armed forces, food shortages and rationing, the assumption of male work roles by numerous women, all impacted upon urban parks and green spaces. As we shall see, public parks in Derby and other places were requisitioned for various purposes including military (such as anti- Zeppelin and aircraft guns), defensive, governmental, medical and for food production, particularly after the Defence of the Realm Act or (DORA) was passed. They also played an important role in maintaining morale when some other forms of recreation were curtailed such as organised sports like football and rugby. At the same time, parks were places where civilian and military populations on leave or recuperating could temporarily escape from some of the demands of war and even resist authority. On occasion they served as venues for anti-war and pacifist meetings and demonstrations too.

The event is free but spaces are limited so if you are interested in attending, please let us know by emailing hiddenhistories@nottingham.ac.uk

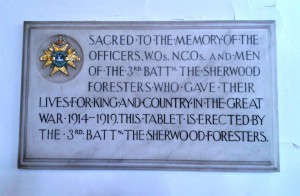

One of our main aims at the Centre for Hidden Histories is to support local groups and societies keen to commemorate the role of their communities in the First World War.

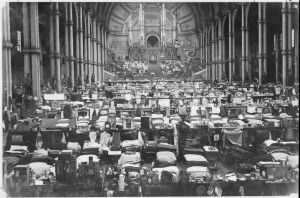

One of our main aims at the Centre for Hidden Histories is to support local groups and societies keen to commemorate the role of their communities in the First World War. The event was held at the Library of Birmingham (see photo), one of the city’s flagship buildings and a really important community space.

The event was held at the Library of Birmingham (see photo), one of the city’s flagship buildings and a really important community space.