The story of Walter Tull is one that resonates strongly today, but was he really the British Army’s first black officer? Michael Noble looks at a curious hidden history.

It was announced this week that Walter Tull, widely regarded as the British Army’s first black officer, is to be commemorated on a special £5 coin, part of a set of six that the Royal Mint will be producing as part of the First World War centenary. This follows the announcement in June that a new road in his home town of Folkestone is to be named Walter Tull way in his honour. Meanwhile, a campaign is underway to make him a posthumous award of the Military Cross that was denied to him while he was alive.

The demand to award Tull the medal is no post hoc rewriting of history, or even a simple response to his fame as a professional footballer. The honour is entirely deserved and its denial a miscarriage of justice. On New Year’s Day 1918 Tull, then a 2nd Lieutenant on the Italian Front, led a mission across the icy-cold River Piave that runs from the Alps to the Adriatic. He returned without a single casualty and was cited by his commanding officer for ‘gallantry and coolness under fire’. The CO recommended that this be followed by a medal. None was forthcoming.

Wars are confusing, challenging situations and many things can go wrong. Still, it’s difficult to shake the conviction that the denial of Tull’s medal was entirely a question of race. The MC was a medal that had been created for junior officers below the rank of Captain and, gallant or otherwise, Walter Tull shouldn’t have been an officer at all. In some eyes, it was bad enough that he was in uniform at all, never mind being given a position of leadership.

The Manual of Military Law of the time stated that ‘Troops formed of coloured tribes and barbarous races should not be employed in war between civilised states’, meaning that sending a man like Tull to fight Germans was anathema to the mindset of the age. Of course, British men of African origin volunteered like any others but according to Tull’s biographer Phil Vasili, ploys were used to ensure that they failed the medical on spurious grounds. This trick, of course, could hardly be deployed against a professional footballer who continued to turn out for Northampton Town throughout the recruitment process and consequently, on completion of the 1914-15 season, Tull attended basic training and was deployed in France that autumn. His abilities were quickly noted and he was made an NCO, attaining the rank of lance sergeant. It would not be the last recognition of his leadership skills, nor would it be the last time he surmounted the institutionalised and statutory racism of the day.

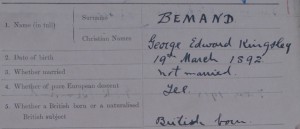

On being recommended for a commission in November 1916, Tull’s commanding officer had to complete a form to begin the process. The document survives and is kept in the National Archives. One of the questions asks if the candidate is of ‘pure European descent’, by which it means white. Tull’s form naturally shows the handwritten response ‘no’. For some reason, Tull’s fame, his exceptional character, the need for men of proven ability, the question was skimmed over by the board and Tull was given his commission in May 1917 whereupon he commenced officer training.

It is curious that the question was even asked. If it was axiomatic that men of non-European backgrounds were inappropriate to serve as officers is seems odd that officers in the British Army would need reminding. But then, not everything in a vast bureaucracy like the modern military is so clear cut. Which brings us to the story of George Edward Kingsley Bermand.

George Bermand was an old boy of Dulwich College, a former engineering student at University College London and, it was said, ‘a cheery soul, always inclined for a joke’. He joined the Officer Training Corps in October 1914, applied for a commission early in 1915 and obtained one with relative ease. He was also black.

The Great War London blog contains some excellent research on Bermand’s life and career. He was born in Jamaica in 1892 and travelled to Britain in 1908. Like Walter Tull, George Bermand was actually of mixed heritage and had some white British ancestry. Still, in accordance with the sensibilities of the time, he and his family were recorded as simply ‘African’ in the form that they completed on the USA leg of their journey to Europe.

The interpretation of such questions is important. When asked if he was of ‘pure European descent’, Walter Tull (or whoever processed his application) answered ‘no’. When George Bermand was asked the very same question, he answered ‘yes’. Bermand’s commission was sponsored by a Brigadier-General Anthony Abdy, who commanded the 30th (County Palatine) Divisional Artillery to which Bermand made his application. ‘I am willing to take him’, noted the Brigadier-General on the form and this seemed sufficient to ensure that Bermand got his commission. It is entirely possible that it was Abdy’s personal intervention that made the question of European descent an irrelevance in Bermand’s case. The bold ‘yes’ merely met a cold bureaucratic requirement leaving the actual business of recruiting a promising young officer to the pleasure of the man who would command him.

Neither Tull nor Bermand survived the war. Bermand was killed by an artillery shell near Bethune on Boxing Day 1916. Tull was cut down by a German soldier during the Spring Offensive of 1918. They were aged 24 and 30 years old respectively.

The recent flurry of activity aimed at commemorating Walter Tull is admirable. His achievements in overcoming unimaginable prejudice on both the field of play and the field of battle are an indication of his strength of character and confirm his as a story worth telling and worth remembering. But there are other stories, other Hidden Histories that show that Tull may not have been alone. Although he was a fine cricketer at Dulwich, George Bermand lacked Walter Tull’s outstanding sporting ability and consequent popular fame. His elevation to officer rank came via the traditional method of patronage while Tull’s was the gift of the newer power of celebrity. Still, that either young man required any assistance to take an officer’s rank remains an indictment of the times in which they lived. In an age that was desperate for healthy young men to answer the country’s call, that any capable candidate would need a nod and a wink to get through the recruitment process seems absurd. But get through they did, and they showed that their places were not mere gifts -they had been earned. Just as Walter Tull earned his Military Cross.

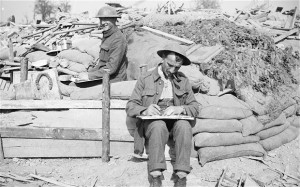

sending its young men off to fight on land, sea and air, by contributing materially to the war effort or by banding together as the costs of the conflict grew, every corner of the country was affected in some way by the First World War. The local impact of the war remains a powerful one and is central to the

sending its young men off to fight on land, sea and air, by contributing materially to the war effort or by banding together as the costs of the conflict grew, every corner of the country was affected in some way by the First World War. The local impact of the war remains a powerful one and is central to the